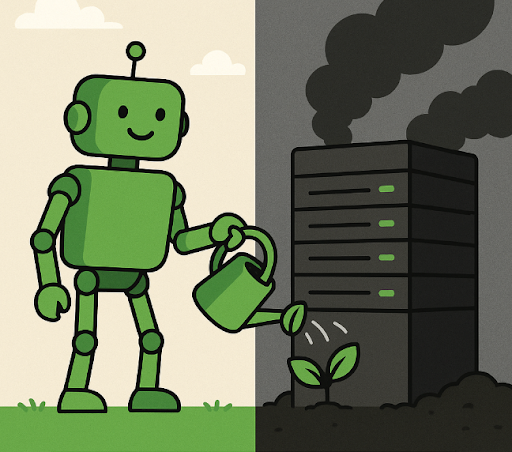

We live in a world surrounded by two opposing forces: the urgent call to protect our planet, and the irresistible pull of new technology. On one hand, we recycle our glass bottles, install solar panels, and swap plastic straws for reusable ones. On the other, we crave the latest smartphones, appliances that work on their own, and cars that can drive themselves.

In the last few decades, our awareness of our environmental footprint has grown enormously. Today, being gentle with the environment feels almost second nature for many of us, though there’s still a long way to go. Solar panels now gleam on rooftops, compost bins sit in gardens, and zero-waste businesses pop up in neighborhoods. People grow their own vegetables or keep chickens to eat more consciously, while electric and hybrid cars are beginning to rival their petrol-powered counterparts on the road. In fact, the US Energy Information Administration indicated in May that about 22% of light-duty vehicles sold in the first quarter of this year in the United States were hybrid, battery electric, or plug-in hybrid vehicles, up from about 18% in the first quarter of 2024.

We’ve made real progress in reshaping our daily habits, but our appetite for modern convenience is just as strong, and it comes with hidden costs. Every smart device, online service, or “intelligent” feature relies on vast networks of servers, data centers, and energy-hungry systems. While these technologies often feel clean and weightless, existing only in the digital world, the truth is they leave a very real footprint on our physical one.

Yes, the fridge can now write your grocery list, and the car is so smart it can parallel park itself, but have you thought about the environmental cost of those “little” smart features? If this has never crossed your mind, brace yourself and keep reading, because there's bad, scratch that, shocking news for you.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is powered by massive amounts of energy, and much of that energy comes from burning fossil fuels, the biggest contributor to global warming. The International Energy Agency estimates that by 2026, electricity consumption by data centers, cryptocurrency, and artificial intelligence could reach 4% of annual global energy usage, roughly equal to the amount of electricity used by the entire country of Japan.

The computational power required to train generative AI models that often have billions of parameters, such as OpenAI’s GPT-4, can demand a staggering amount of electricity, which leads to increased carbon dioxide emissions and pressures on the electric grid. Furthermore, deploying these models in real-world applications, enabling millions to use generative AI in their daily lives, and then fine-tuning them to improve performance draws large amounts of energy long after a model has been developed.

Beyond electricity demands, a great deal of water is needed to cool the data centers and hardware used for training, deploying, and fine-tuning generative AI models, which can strain municipal water supplies and disrupt local ecosystems. The increasing number of generative AI applications has also spurred demand for high-performance data centers, adding indirect environmental impacts from their manufacture and transport.

A data center is a temperature-controlled building that houses computing infrastructure, such as servers, data storage drives, and network equipment. For instance, Amazon has more than 100 data centers worldwide, each of which has about 50,000 servers that the company uses to support cloud computing services. And this is just Amazon, but there are many others; the pace at which companies are building new data centers means the bulk of the electricity to power them must come from fossil fuel-based power plants.

Scientists estimate that the power requirements of data centers in North America increased from 2,688 megawatts at the end of 2022 to 5,341 megawatts at the end of 2023, partly driven by the demands of generative AI. Globally, the electricity consumption of data centers rose to 460 terawatt-hours in 2022. This would have made data centers the 11th-largest electricity consumer in the world, between Saudi Arabia (371 terawatt-hours) and France (463 terawatt-hours), according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

The generation of electricity, particularly through fossil fuel combustion, results in local air pollution, thermal pollution in water bodies, and the production of solid wastes, including even hazardous materials. Elevated carbon emissions in a region come with localized social costs, potentially leading to higher levels of ozone, particulate matter, and premature mortality.

And beyond its energy usage, AI also requires hardware. The production, transport, maintenance, and disposal of servers and other components require additional energy and substantial natural resources such as cobalt, silicon, and gold. The mining and production of these metals can lead to soil erosion and pollution. Many electronics are not properly recycled, leading to electronic waste that contaminates soil and water when not disposed of correctly.

Furthermore, once a generative AI model is trained, the energy demands don’t disappear. Each time a model is used, perhaps by an individual asking ChatGPT to summarize an email, the computing hardware that performs those operations consumes energy. It’s estimated that a ChatGPT query consumes about five times more electricity than a simple web search. Plus, generative AI models have an especially short shelf life, driven by rising demand for new applications. Companies release new models every few weeks, so the energy used to train prior versions goes to waste. New models often consume even more energy for training, since they usually have more parameters than their predecessors. So we find ourselves in a never-ending circle.

However, not all hope is lost! While these numbers might seem daunting, the story doesn’t end here. Around the world, scientists, engineers, and policy makers are already working to make artificial intelligence part of the climate solution, not just the problem.

We’ll be returning to this topic soon to look at what a greener AI future might actually look like, what’s already being done, and how each of us can help get there.

Until then, may your gadgets be clever, and your carbon light.