Campus-Wide Generative AI Survey: Executive Report

July 2024

Prepared by:

DIT: Megan C. Masters, PhD; Jonathan Engelberg, PhD; Alia Lancaster, PhD

IRPA: Jess Wojton; with thanks to Alan Socha, PhD, and Danielle Glazer

The 2023-2024 academic year represented the first full year in which Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools were readily available for use across the entire campus community. To gain a baseline understanding of students’ and instructors’ familiarity and use of GenAI tools within academic and instructional contexts, parallel surveys were administered to students (n = 38,612) and instructors (n = 3,726) in Spring 2024. Sixteen percent of instructors and five percent of students responded to the survey.1 The higher response rate associated with the instructor population is considered appropriate, particularly given that the surveys were administered by the Division of Information Technology, in partnership with the Division of Academic Affairs, which oversees the instructional faculty that set the policy, guidelines, and tone around students’ use of GenAI tools within academic contexts. Generalizations to the larger UMD population will be made with caution when interpreting student trends in particular.

This executive report contains the main findings and supporting data for each main finding. For more details, please read the compendium. Please note that, while the findings presented here correspond to all respondents, a few pertain only to respondents who identified themselves as routine users of GenAI within academic contexts. This distinction will be appropriately noted within the report.

Main Findings

- Overall, most student and instructor respondents have experimented with GenAI tools across a variety of contexts. Both groups reported using GenAI tools for personal projects, academic work, and to assist with research activities.

- Most student and instructor respondents do not routinely use GenAI tools in academic contexts. Graduate student respondents appear to embrace this new technology more, as a higher percentage routinely use it for academic work compared to undergraduate student respondents.

- Among respondents who routinely use GenAI, a singular academic or instructional use does not stand out. Whether for academic or instructional use, routine GenAI users leverage these tools for a number of different purposes, including generating ideas, improving content, and summarizing concepts.

- Academic integrity is a main concern for student respondents, but student respondents are more confident in their ability to use GenAI within established standards than instructor respondents believe they are.

- Most student and instructor respondents are discussing GenAI tools in classes, although guidance on application varies from instructor to instructor. Student respondents experience everything from outright bans to active encouragement from instructors to use GenAI tools.

- About half of student and instructor respondents anticipate greater GenAI use in subsequent semesters, and there are opportunities for future educational efforts. Both quantitative and qualitative data collected through the current GenAI survey can provide starting points for anticipated GenAI initiatives related to teaching and learning.

Finding 1: Overall, most student and instructor respondents have experimented with GenAI tools across a variety of contexts.

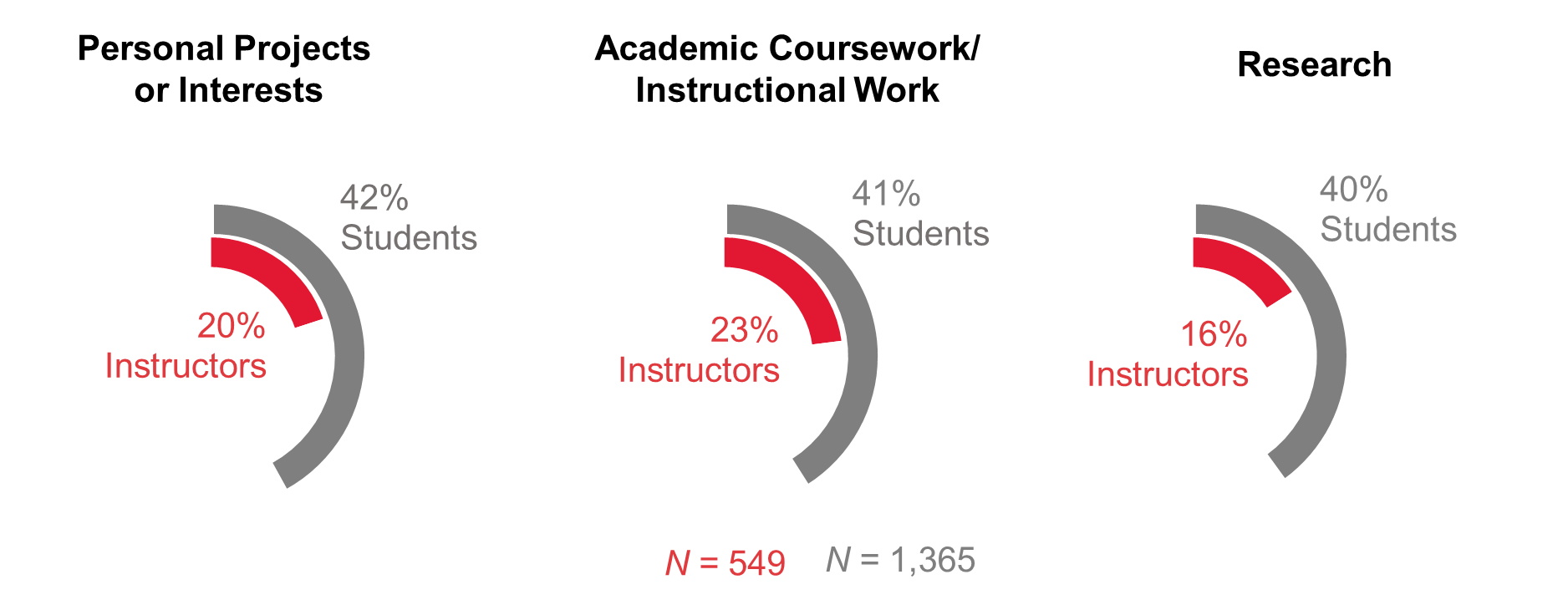

Over three-quarters (77%) of student respondents and over half (55%) of instructor respondents indicated that they had used GenAI in at least one context.2 The top three contexts in which student and instructor respondents use GenAI included personal projects or interests, academic coursework/instructional work, and research (Figure 1), but fewer than half of respondents use GenAI in any one of these contexts. A higher percentage of student respondents reported using GenAI than instructor respondents. For example, 41% of student respondents typically use GenAI in academic coursework, while 23% of instructor respondents engage with GenAI for instructional work.3

Student and instructor respondents selected personal projects, academics, and research as the top three contexts in which they used GenAI tools, although only a minority of each group use it within each context.

Figure 1. Student and instructor respondents' selections to the question “Broadly speaking, within which contexts do you typically use GenAI tools?” in the top three most selected categories for each group.

Finding 2: Most student and instructor respondents do not routinely use GenAI tools in academic contexts.

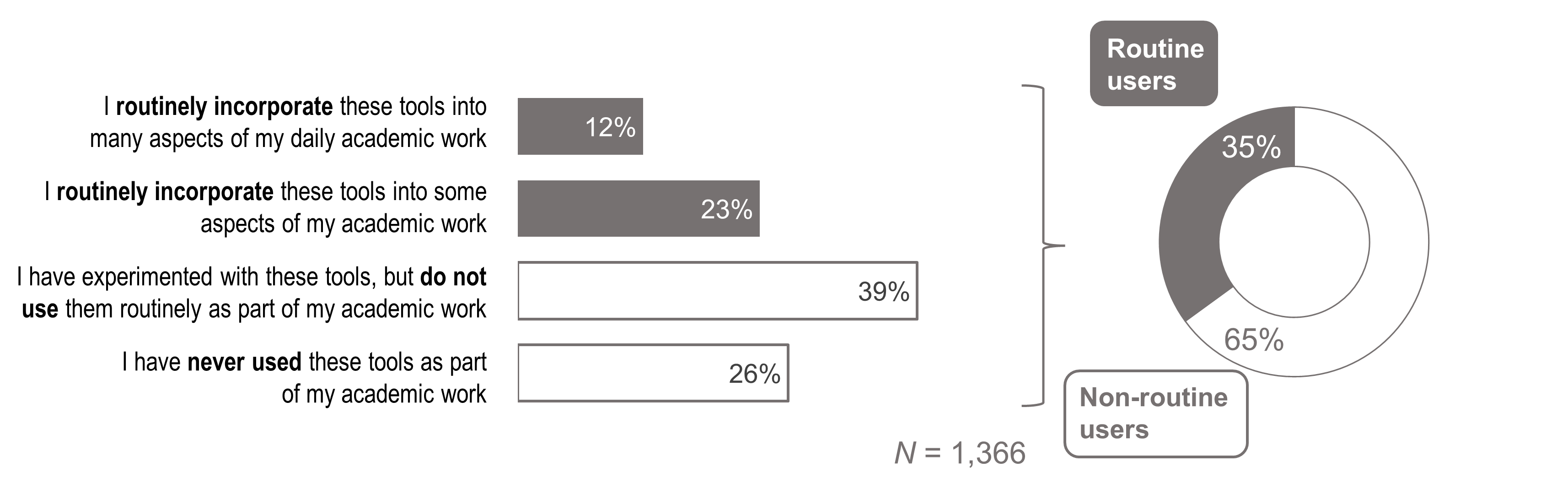

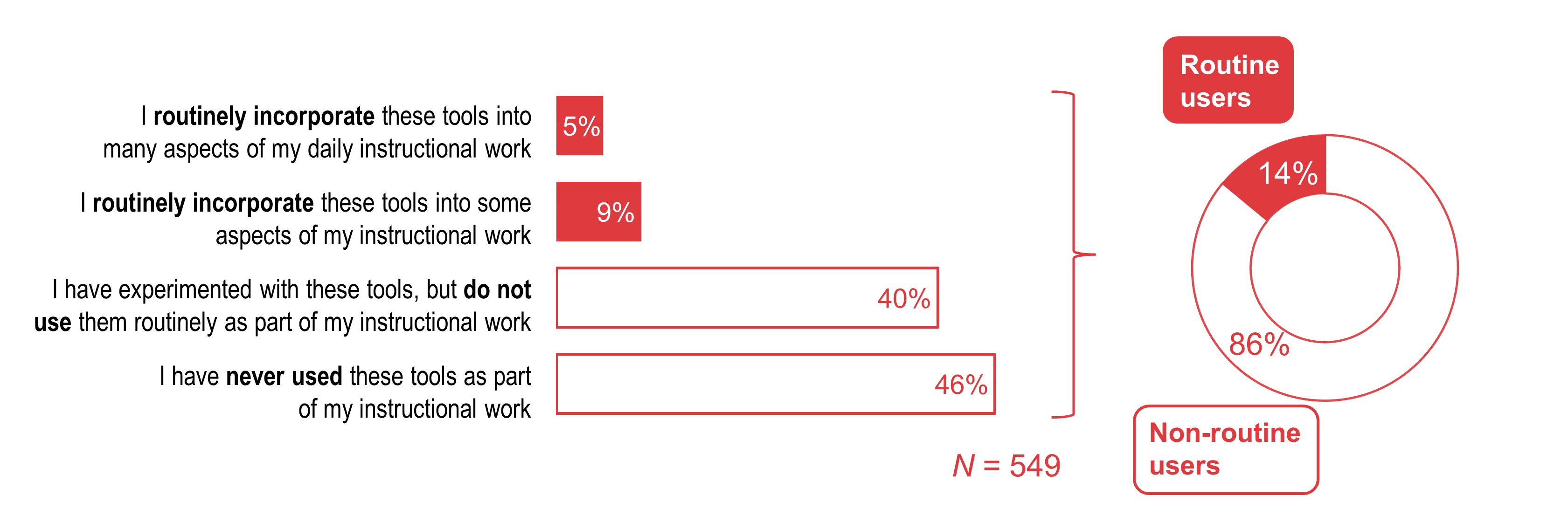

Given that the purpose of this survey was to collect baseline data related to student and instructor respondents’ perceptions of the integration of GenAI tools within academic contexts, one question was asked specifically about how frequently respondents use GenAI tools. Only about a third of student respondents (35%) and 14% of instructor respondents said they routinely incorporate GenAI in some or many aspects of their academic or instructional work (Figures 2 and 3).

65% of student respondents report not using GenAI for academic work routinely.

Figure 2. Student respondent selections to the question “How would you describe your use of GenAI tools in your academic work?”

Similarly, most instructor respondents characterize themselves as non-routine users of GenAI for instructional work.

Figure 3. Instructor respondent selections to the question “How would you describe your use of GenAI tools in your instructional work?”

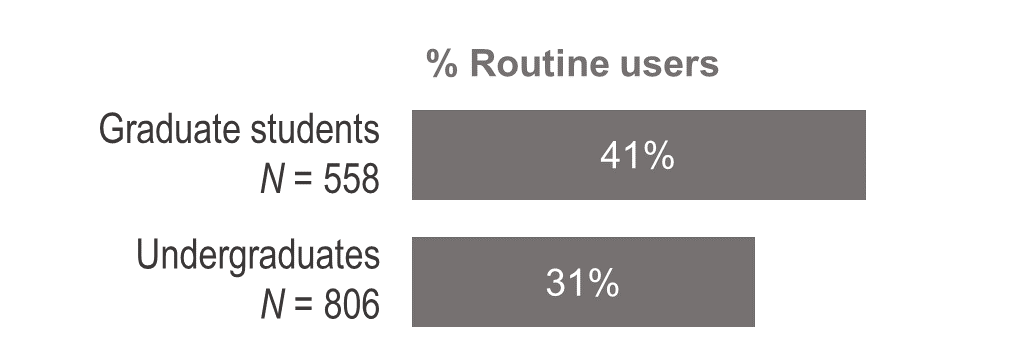

Graduate student respondents report using GenAI more than undergraduate student respondents, both overall, and as it relates to routine academic work (see Figure 4). For additional comparisons of routine and non-routine GenAI users within academic contexts, please see the compendium.

A higher percentage of graduate student respondents reported routinely using GenAI for academic work than undergraduate students.

Figure 4. Undergraduate and graduate student responses to the question “How would you describe your use of GenAI tools in your academic work?” grouped by their response to the question in Figure 2.

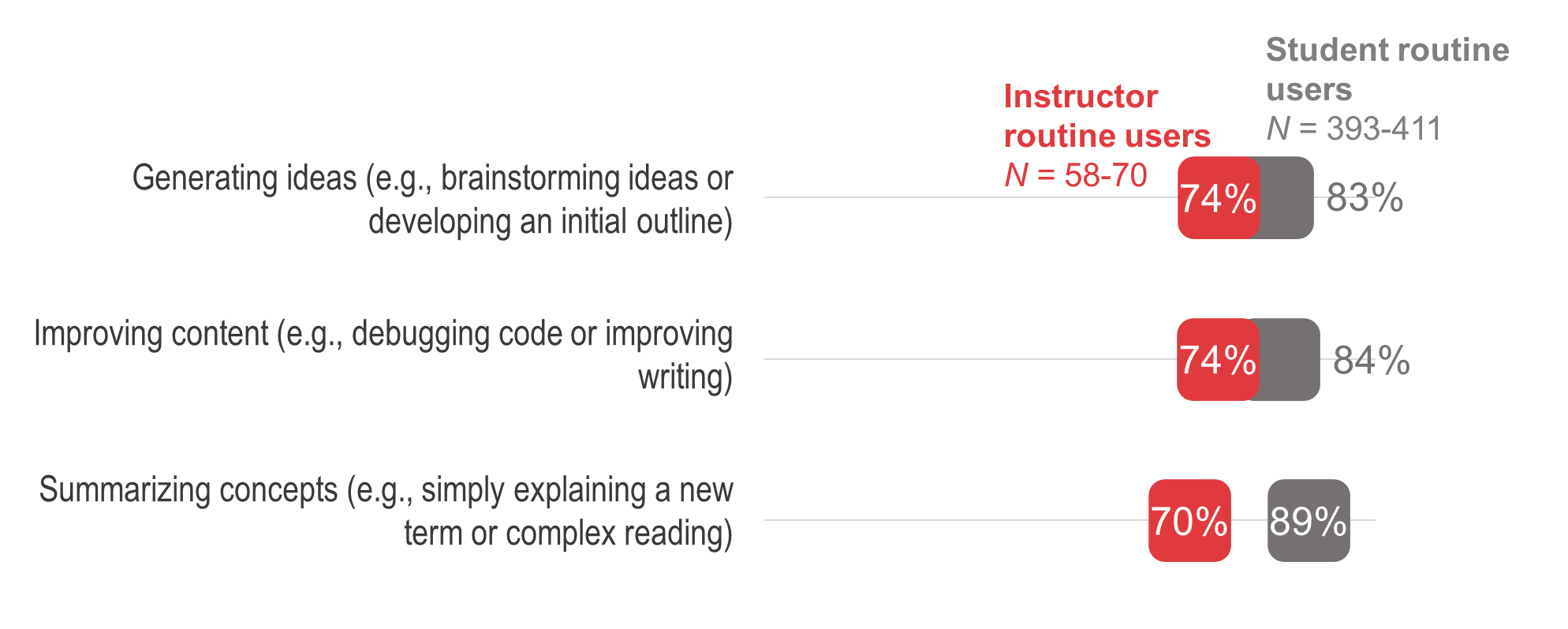

Finding 3: Among respondents who routinely use GenAI, a singular academic or instructional purpose does not stand out.

For routine GenAI users, whether for academic or instructional use, student and instructor respondents use the technology for a variety of purposes. The top three uses for both groups are shown in Figure 5.

Most routine users of GenAI incorporate it for generating ideas, improving content, and summarizing concepts.

Figure 5. Top three respondent selections to the question “Have you used GenAI for the following academic/instructional purposes?” from student and instructor routine users of GenAI in academic contexts.

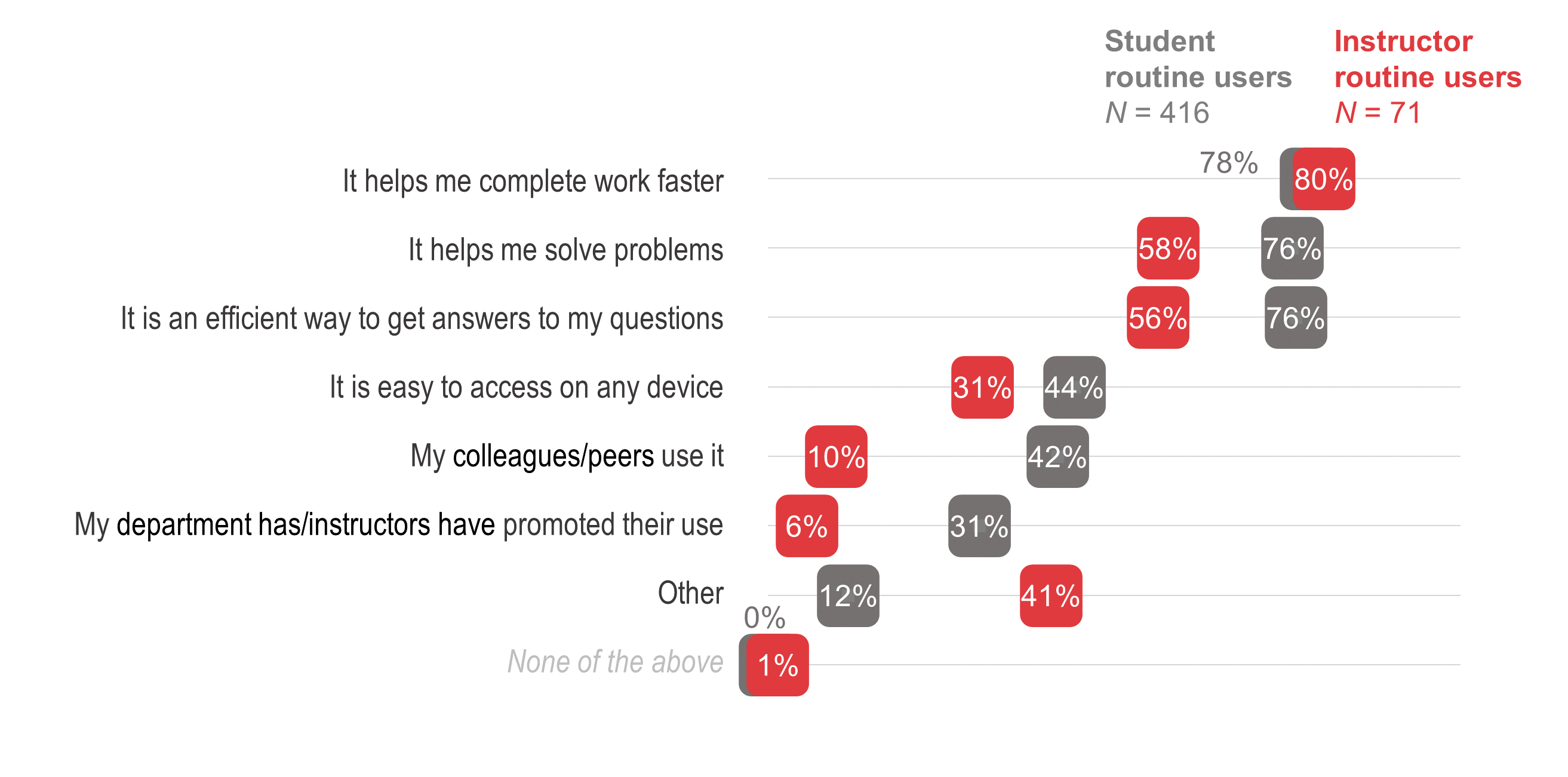

When asked about the factors motivating their use of GenAI tools in academic or instructional contexts, both student and instructor respondents identified ways in which GenAI enhances their work, including helping them complete work faster, solving problems, or answering questions efficiently (Figure 6). Social factors, such as the use of GenAI by colleagues or peers, or the promotion of GenAI by departments or instructors, played a smaller role, especially among instructor respondents. This may partly reflect that few instructor respondents currently use GenAI routinely, so there might not exist a critical mass of instructor peers to exert influence (whereas more student respondents use it, and relatively more student respondents cite the use of GenAI by peers as a motivating factor).

Student and instructor respondents use GenAI to complete work faster, solve problems, and answer questions.

Figure 6. Responses from student and instructor routine users of GenAI in academic contexts to the question “Turning to your use of GenAI tools within academic/instructional contexts specifically, what motivates you to use GenAI tools?”

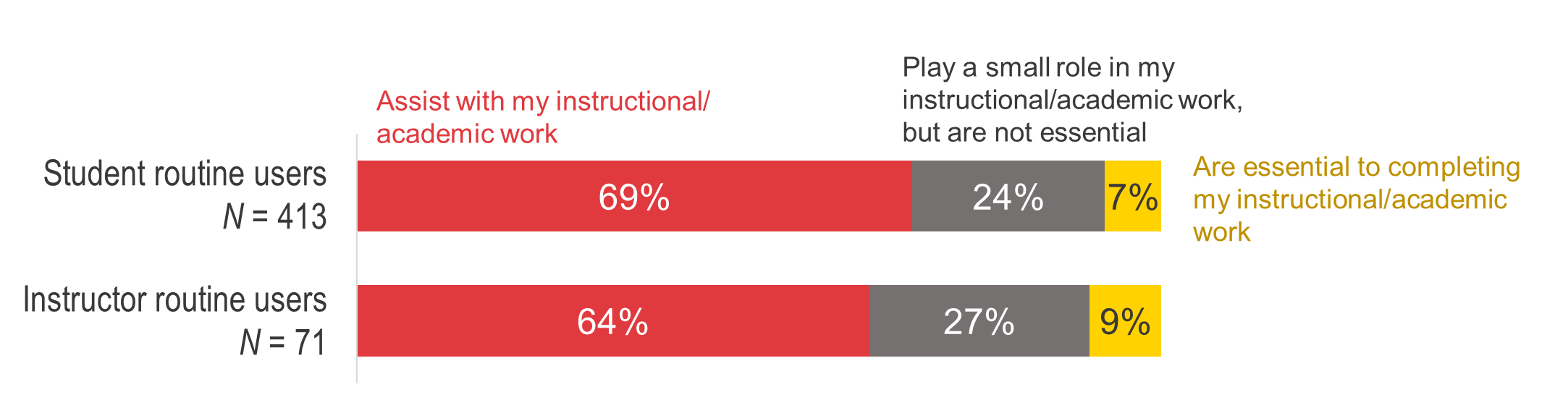

Routine users seem to use GenAI tools with discretion. Nearly three-quarters of routine GenAI users (75% of student and 72% of instructor respondents) employ external sources to validate GenAI output. Turning to the extent to which student and instructor respondents integrate GenAI tools into their academic routines, both groups indicated that they use the tools to facilitate their work, as shown in Figure 7.

Most student and instructor respondents use GenAI to assist with their academic/instructional work.

Figure 7. Instructor and student routine user responses to the question “Overall, which statement best characterizes how much you rely on the use of GenAI tools for your instructional/academic work?”

Finding 4: Although academic integrity is a main concern, student respondents are more confident in their ability to use GenAI within established university standards than instructor respondents believe students are.

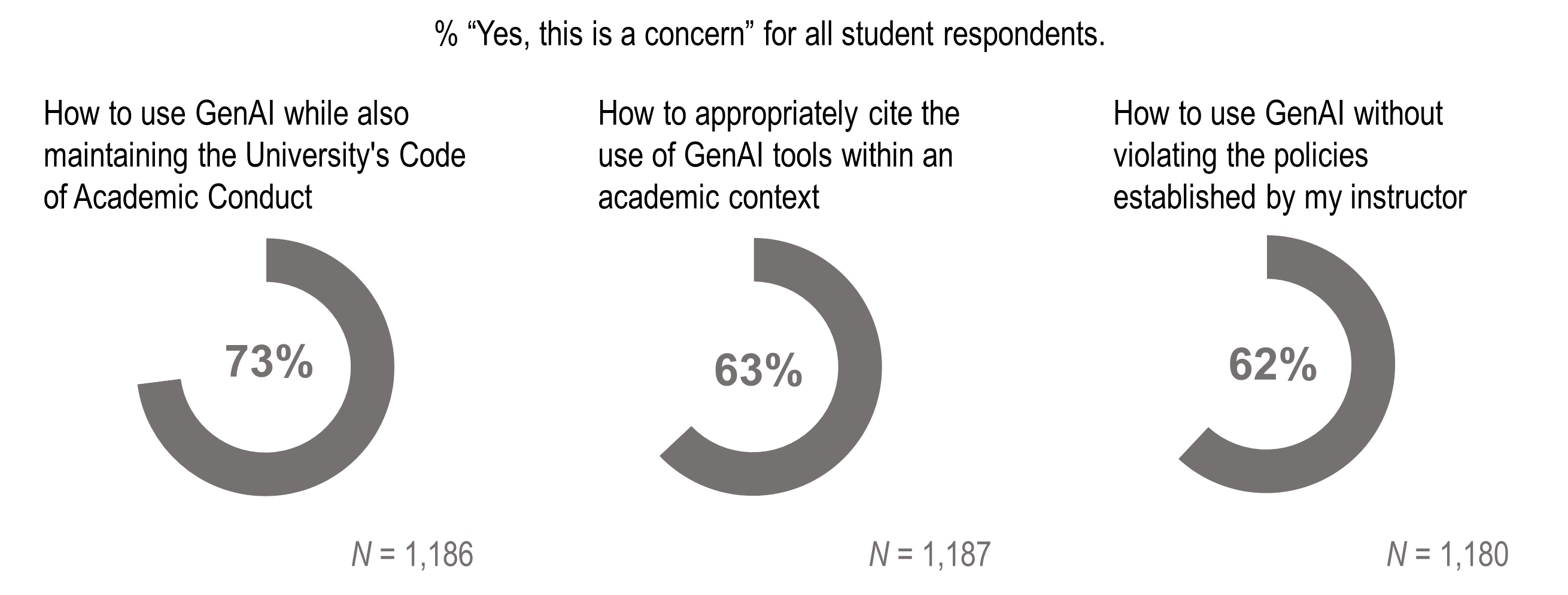

The remainder of the results discussed reference all student and instructor respondents, unless otherwise noted. Concerns about violating the University Code of Academic Conduct, violating instructors’ policies, or appropriately citing the use of GenAI tools ranked high among student respondents, suggesting that responsible use is an important issue to them (Figure 8). Approximately a third of student respondents (31%) also selected “Other” to the list of concerns provided, with an option to write in their specific concern. A thematic analysis revealed the most commonly cited “Other” theme among student respondents involved broader ethical concerns related to GenAI, such as concerns about how GenAI models are trained on copywritten or original work. Therefore, while using GenAI responsibly within academic contexts is important to students, so too is their responsible use of it more broadly.

The remainder of the results discussed reference all student and instructor respondents, unless otherwise noted. Concerns about violating the University Code of Academic Conduct, violating instructors’ policies, or appropriately citing the use of GenAI tools ranked high among student respondents, suggesting that responsible use is an important issue to them (Figure 8). Approximately a third of student respondents (31%) also selected “Other” to the list of concerns provided, with an option to write in their specific concern. A thematic analysis revealed the most commonly cited “Other” theme among student respondents involved broader ethical concerns related to GenAI, such as concerns about how GenAI models are trained on copywritten or original work. Therefore, while using GenAI responsibly within academic contexts is important to students, so too is their responsible use of it more broadly.

Most student respondents have concerns about how to use GenAI tools responsibly according to university and instructor policies.

Figure 8. Percentage of student respondents who indicated “Yes, this is a concern.” The overarching question was: “The following items are commonly cited questions related to the use of GenAI tools within an academic context. Please indicate which (if any) are related to your decision not to use GenAI tools as part of your academic work:”

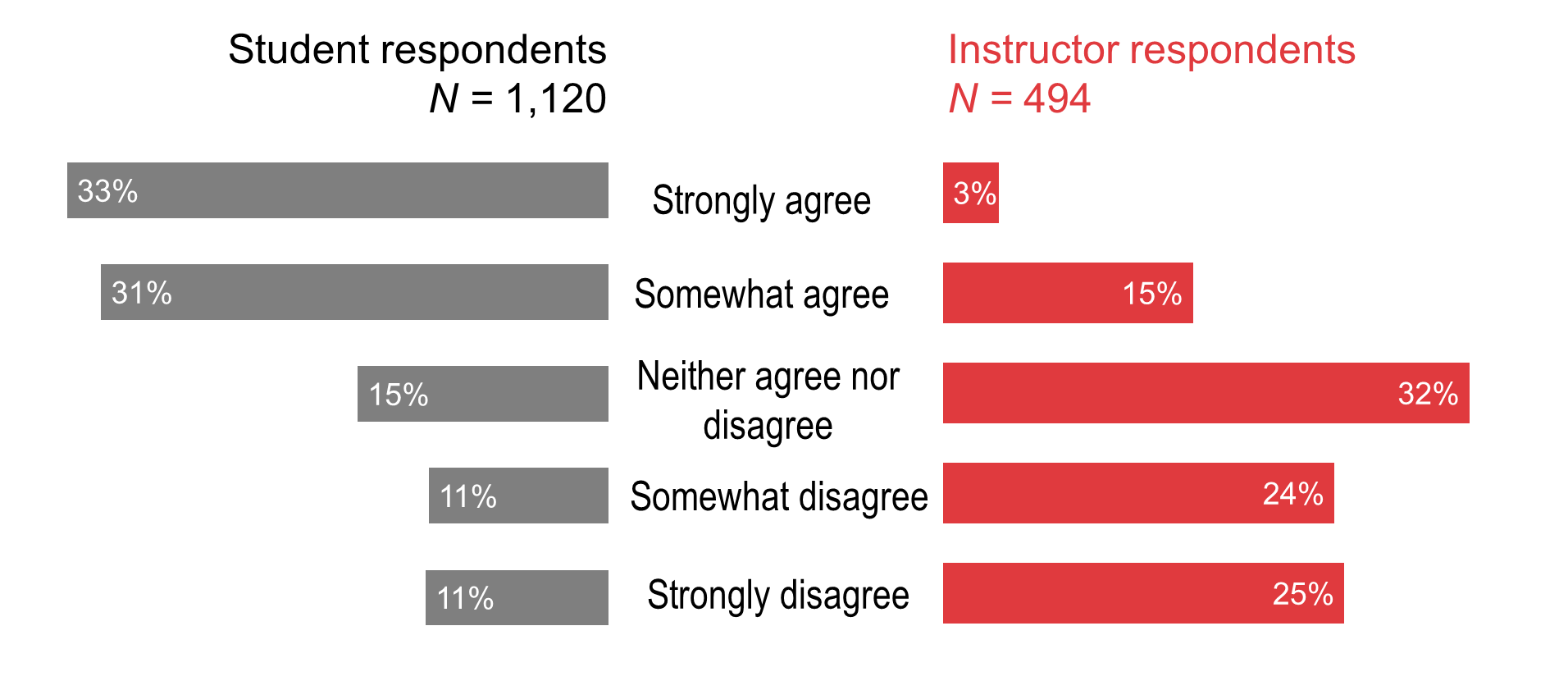

While the topic of responsible use of GenAI tools is on student respondents’ minds, there does appear to be a disconnect between student and instructor respondents’ perceptions of students' ability to use GenAI responsibly (Figure 9). When given the opportunity to write in concerns about GenAI, the most commonly occurring theme among instructor respondents - but not student respondents - was related to perceived or potential violations of academic integrity by students.

64% of student respondents agree that they understand how to use GenAI responsibly, while only 16% of instructor respondents believe students do so.

Figure 9. Student and instructor respondent selections to the question, “Please indicate your agreement with the following statement: I/my students understand how to appropriately use GenAI tools within my/their academic work so that I/they maintain academic integrity standards.”

Finding 5: Most student and instructor respondents are discussing GenAI tools in their classes, although guidance on application varies from instructor to instructor.

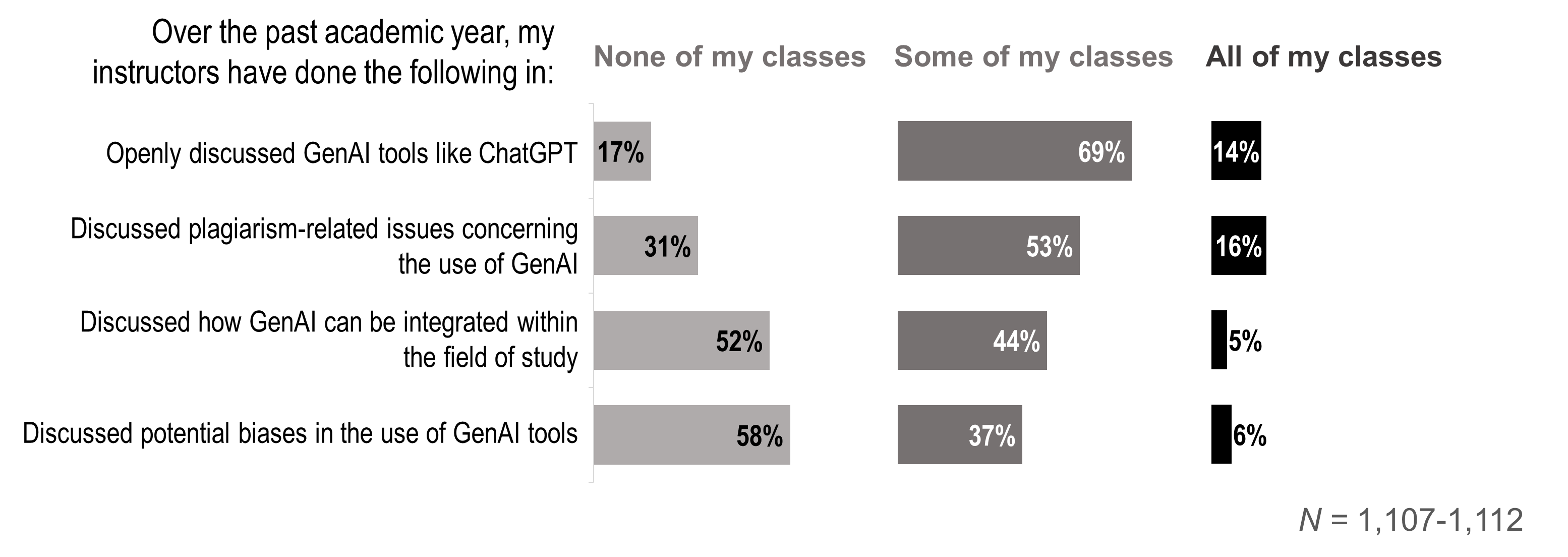

Most student (83%) and instructor (71%) respondents reported discussing tools such as ChatGPT in some or all of their classes in the last academic year (see Figure 10 for student responses to questions about discussions of GenAI in the classroom).

While discussions around ChatGPT and plagiarism are a common experience for student respondents, discussions about integrating GenAI and its potential biases are less common.

Figure 10. Student respondent selections to discussion-based stems of the question “Over the past academic year, my instructors have done the following in (none/some/all) of my classes.”

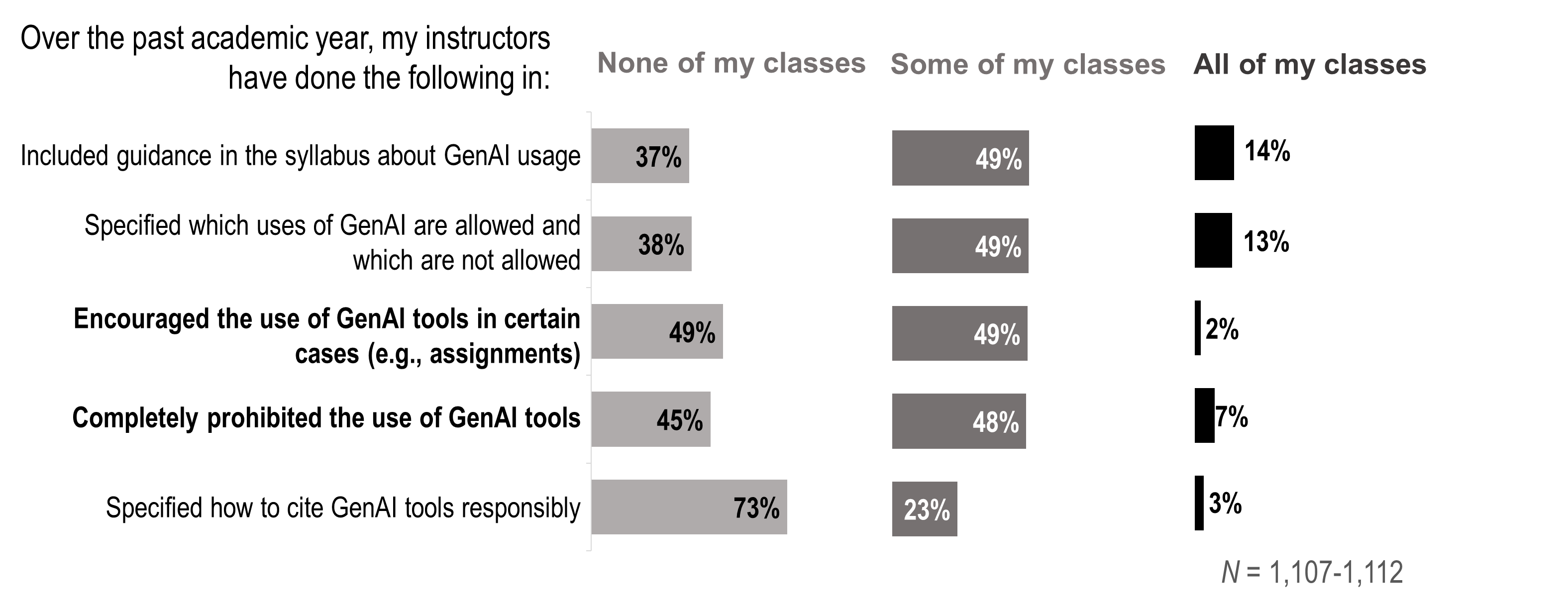

While discussions about GenAI appear widespread, guidance to student respondents about how to apply GenAI within coursework varied (Figure 11). From the instructors’ perspective, almost half of instructor respondents (48%, not pictured) said they have not included guidance about these tools on any of their syllabuses, whereas others incorporate it in ways to explore its limitations with students (see quotes).

Student respondents’ experiences with the integration of GenAI in their classes appears to be random, with half of student respondents reporting encouraged integration of its use and the same percentage of student respondents reporting a complete ban on the use of the technology.

Figure 11. Student respondent selections to guidance-based stems of the question “Over the past academic year, my instructors have done the following in (none/some/all) of my classes.”

Finding 6: Half of student and instructor respondents anticipate greater GenAI use in subsequent semesters, and there are opportunities for future educational efforts.

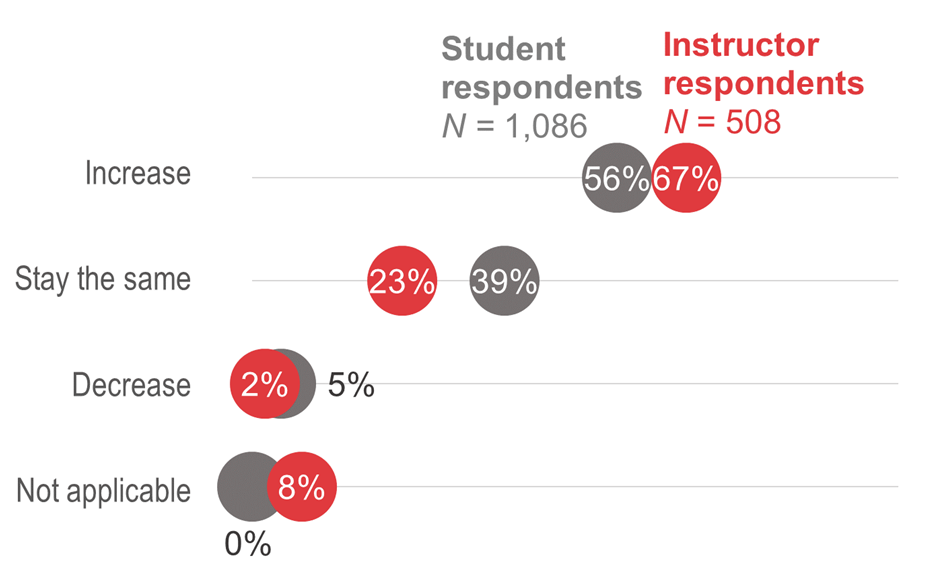

Although a minority of respondents reported using GenAI routinely within academic or instructional contexts, these data represent initial baseline data collected after only a few years of the wide-scale release of a new technology. Routine users and non-routine users alike anticipate using GenAI within academic contexts more in the future (Figure 12).

Most student and instructor respondents expect their future use of GenAI tools to increase.

Figure 12. Responses from all student and instructor respondents (routine and non-routine GenAI users) to the question, “Broadly speaking, do you anticipate that your future use of GenAI tools for teaching/within academic contexts will [increase/stay the same/decrease/not applicable].”

Looking specifically at respondents who reported non-routine use of GenAI technology, two-thirds reported being interested in learning more about GenAI within academic contexts. Student respondents were most interested in learning about assessing GenAI for accuracy and citing the use of GenAI, reflecting their top concerns about academic integrity, while instructor respondents were most interested in information about how to instruct students in incorporating GenAI responsibly. Altogether, these data suggest that usage is likely to increase and that efforts to thoughtfully incorporate GenAI might prove more successful than eliminating its use.

That said, it is worth noting that over a third of student respondents (38%) who use these tools routinely in academic contexts do so without direction from their instructors, and about half of instructor respondents (48%) who use GenAI routinely for instructional purposes said they do so without guidance from their departments or the university. These findings indicate that even among those who use GenAI routinely for academic work, there is still room for additional or more frequent guidance on its use from instructors, departments, and university administration.

Recognizing that the survey was uniquely positioned to capture baseline data from students and instructors after the first academic year in which GenAI was widely introduced, the survey designers experimented with the novel incorporation of an optional five-question “quiz.” This quiz was aimed towards raising awareness of the limitations and considerations to keep in mind when engaging with GenAI as an emerging technology, particularly since the survey itself was administered to the entire student and instructor-of-record populations.4

Results of the quiz questions indicated that 70% of all student and instructor respondents correctly identified the primary method for training models (i.e., using large amounts of existing text and data) and some basic limits in the understanding and awareness of GenAI tools. However, only about 50% of respondents could identify the primary source of training data (i.e., online user-generated content), and most instructor respondents (77%) did not identify themselves as experts in GenAI. These findings highlight student and instructor respondents’ gaps in knowledge that the university can address as a leader in GenAI research and learning opportunities.

Conclusion

Most student and instructor respondents reported that they did not use GenAI tools routinely for academic or instructional purposes. This finding mirrors the reported low use of GenAI for other purposes (e.g., personal projects, research) for each group, although most respondents did report experimenting with GenAI in at least one context. It is certainly possible that some students and instructors who do not use GenAI self-selected out and did not respond to the survey, suggesting that an even lower percentage of these groups use GenAI than reported here. Conversely, student respondents indicated that some instructors outright ban GenAI for coursework, which could have led to student respondent hesitancy in indicating their own use of this new technology for academic purposes. In general, it appears that familiarity, use, and reasons for engaging with these tools are as diverse as the UMD community itself. Student and instructor respondents alike cited everything from ethical concerns to security issues to relevance to the course as reasons why they did or did not engage with these tools.

For those who did use GenAI routinely in academic contexts, student and instructor respondents both reported using these tools to generate ideas, improve content, and summarize concepts. However, instructor respondents have less certainty than student respondents themselves in the ability of students to use GenAI within the University’s academic Code of Conduct. On this topic, using GenAI responsibly was one of student respondents’ main concerns, and their experience of GenAI in the classroom varied greatly. With over half of the respondents within each group indicating that their use of GenAI tools will increase in the future, there are opportunities for the University to provide further guidance and training at all levels on this quickly evolving technology.

1 The higher response rate for instructors relative to students is in line with recent campus-wide survey efforts, such as the nationally benchmarked EDUCAUSE Teaching and Learning with Technology surveys, administered in 2023, which yielded a 15% response rate for instructors and 7% response rate for students, as well as the campus-wide Student and Faculty Experience surveys, administered periodically over the 2020-2022 academic years, showing response rates ranging from 21% - 30% rate for instructors and a 6% - 17% for students. See also Fosnacht, K., Sarraf, S., Howe, E., & Peck, L. K. (2017). How important are high response rates for college surveys? The Review of Higher Education, 40(2), 245-265, which discusses the appropriateness of population generalizability inferences from smaller survey response rates provided that no evidence of systematic non-response bias is found.

2 These percentages were calculated out of all respondents who answered the survey question concerning contexts of use. We believe this is an accurate indication of use by survey respondents, as the response options included an “Other” option, to capture any contexts not listed in the item stems, and a “None of the above” option, which 23% of student respondents and 45% of instructor respondents used.

3 The analysis team examined patterns in respondent characteristics and found no evidence of systematic nonresponse bias, suggesting that the current results may be generalized to the UMD population, with caution. It is important to note, however, that those who are reluctant to indicate that they incorporate GenAI tools for academic or instructional purposes may be less likely to respond to the survey.

4 Answers were provided at the end of the survey along with UMD resources on GenAI for more information.